Hands

of

trinidad

My name is Daryl. Sometimes people assume I’m a man and, sometimes, I don’t bother to correct them. I like the idea of not being the person people think I am.

I moved to Trinidad by accident after misreading a Craigslist ad. It ended up being a kind of pilgrimage. They say that Trinidad births you or aborts you. For me it was a birth and this project was the baby.

My first weekend in town was Cinco de Mayo. Downtown was open late for First Fridays, a monthly art walk in the Creative District. The sun was setting over Main and Commercial and I was counting the bricks stamped with "TRINIDAD" that laid the street. On the corner, the sun bounced off a metal plaque, making it glow like a neon sign.

It was the Aultman Studio commemoration plaque, a father-son photography space that opened in 1890 in one of the buildings across the street. It described an archive called “Faces of Trinidad”. One Google search and over 50,000 faces were staring back at me. Unlike a painting, a photo has the magic of being made with the moment, not of the moment. It is inextricably linked to something that really happened. I was reacquainted with the power of the photograph, written with light from a moment in time. But I was left with the question, ‘What about now?’

After a few conversations with Marggie Ferrendelli, the director of Space to Create, I had my own pop-up portrait studio down the street from the very place this work started. Every First Friday of the month I walked downstairs from my apartment to take black and white analog photos just like they did in 1890.

The pop-up led to pop-ins. I was invited into peoples’ homes, to help on their cattle drives, and to try their family’s Sunday Sauce. Short conversations between portraits became a ceremony of oral history. Meeting someone new lets you meet yourself again. Nothing can do that quite like the process of taking a portrait. With film, there are no sneak previews. I don’t see the images until I develop them in my sink. Subjects don’t see the images until they are printed in the show. What was in the camera is what's on the print – as close to exactly who they were in that sixtieth of a second. No retouching. Perfect is not the point.

We had forgotten about the time we had to wait weeks to see prints. The waiting made it special. With the invention of the digital camera, we did not have to wait anymore. Photographs became instantaneous, but they are now forgotten on cell phones, and die in ‘the cloud’. We did not appreciate the waiting time when we had it. Without it, forgetting has also become instantaneous. This is why I shoot on film.

For me, photographs are artifacts of a moment. A moment is not simply a random slice of time. Time becomes a moment when it is observed, and that moment is a piece of art. Behind the camera, I am only a witness, framing a moment to say: Look at this! This is important! Remember! My art is the art of observation. The true artist is God.

My camera is a tool I use to share my observations. But it is not enough to just take a photo. The photo is meant to be presented and preserved in a way where the community can engage with it, and where the people can see themselves. History is a human right. To me, public art is about allowing communities to participate in their own history.

When I was asked to include this project as a part of the Crossroads Exhibit, organized and funded by the Smithsonian Institute, I knew it was an opportunity to give it the platform it deserved. As rural America continues to shrink, Trinidad continues to show its resilience. This is only possible because of its people.

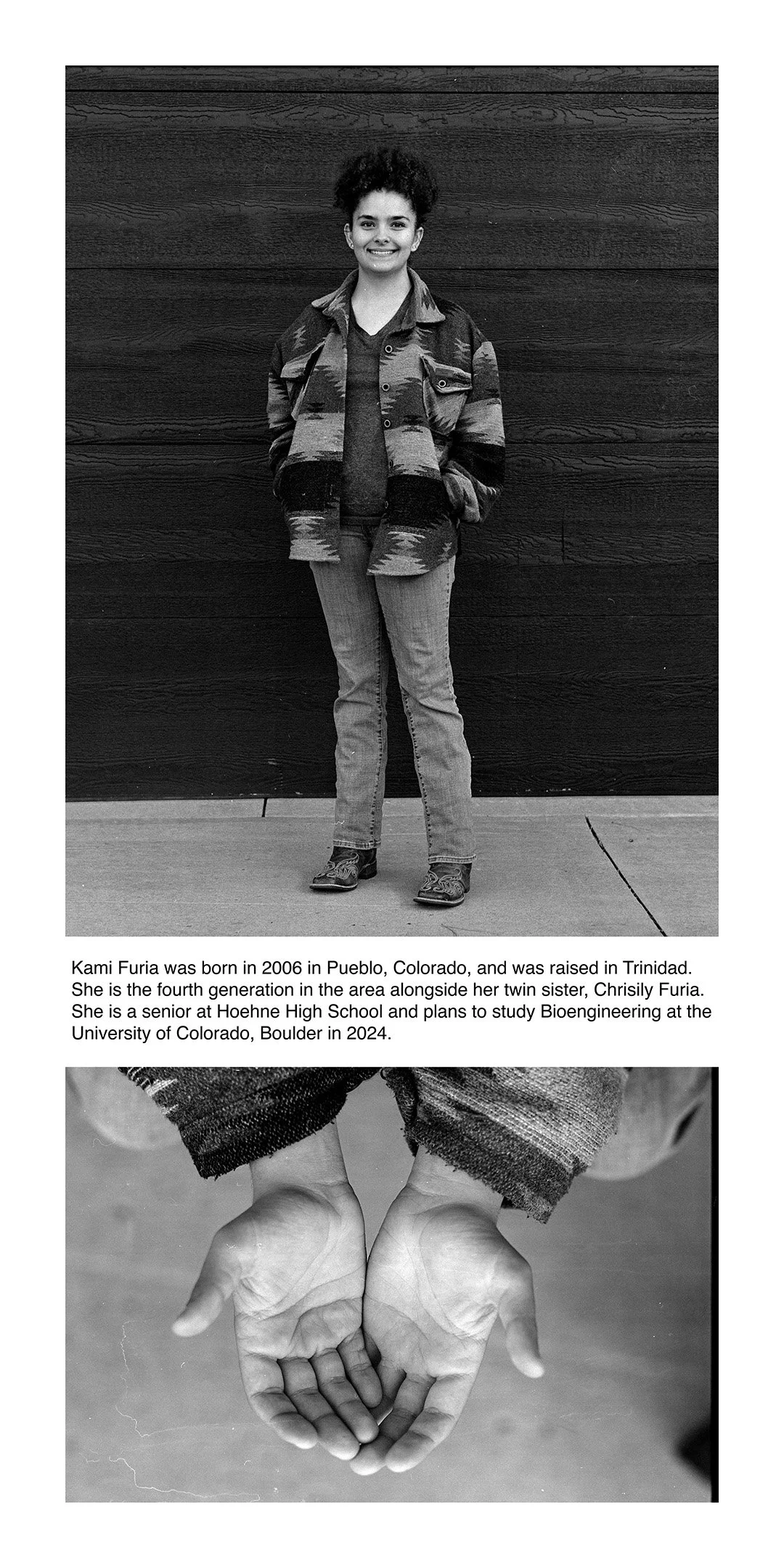

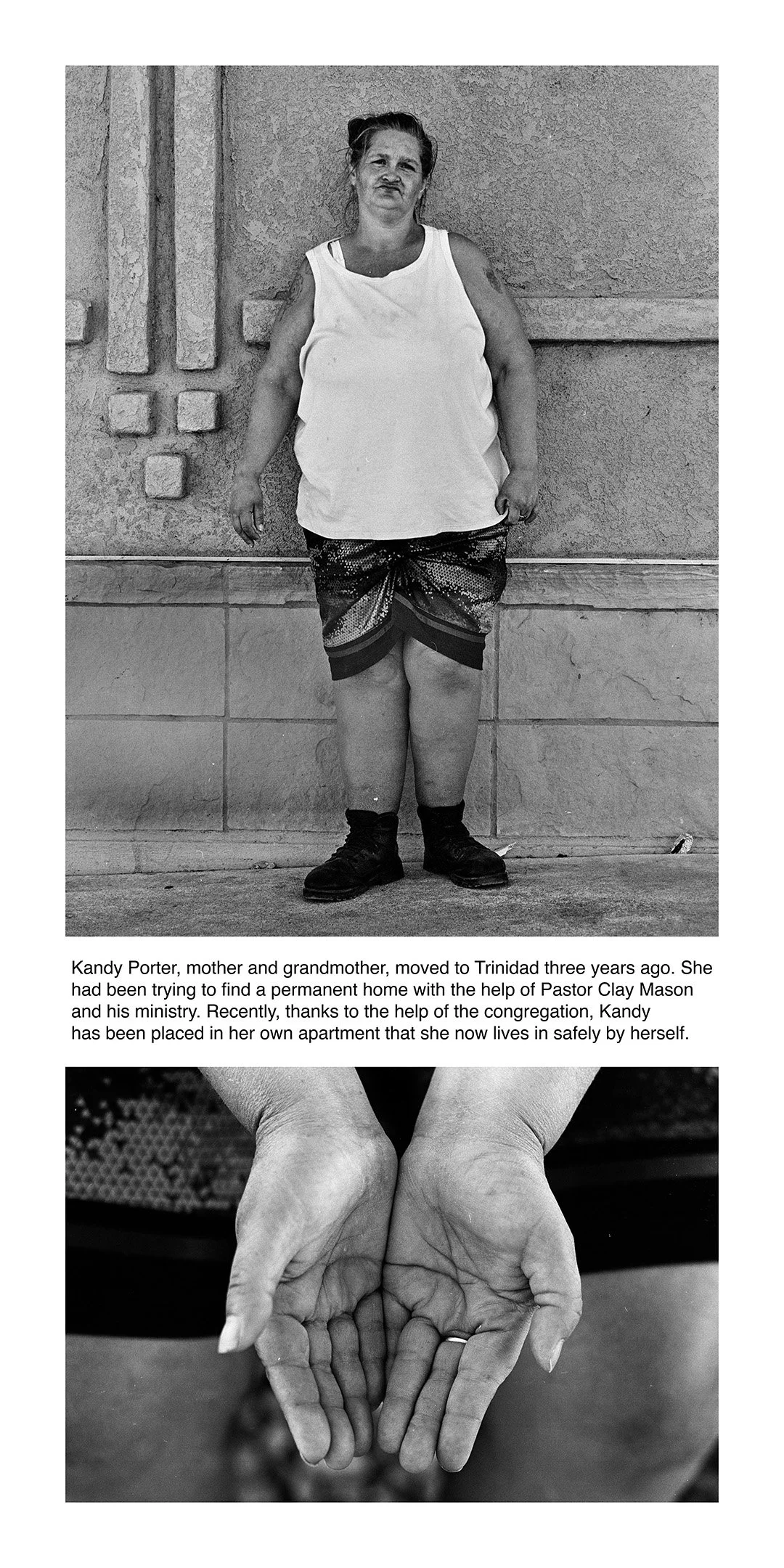

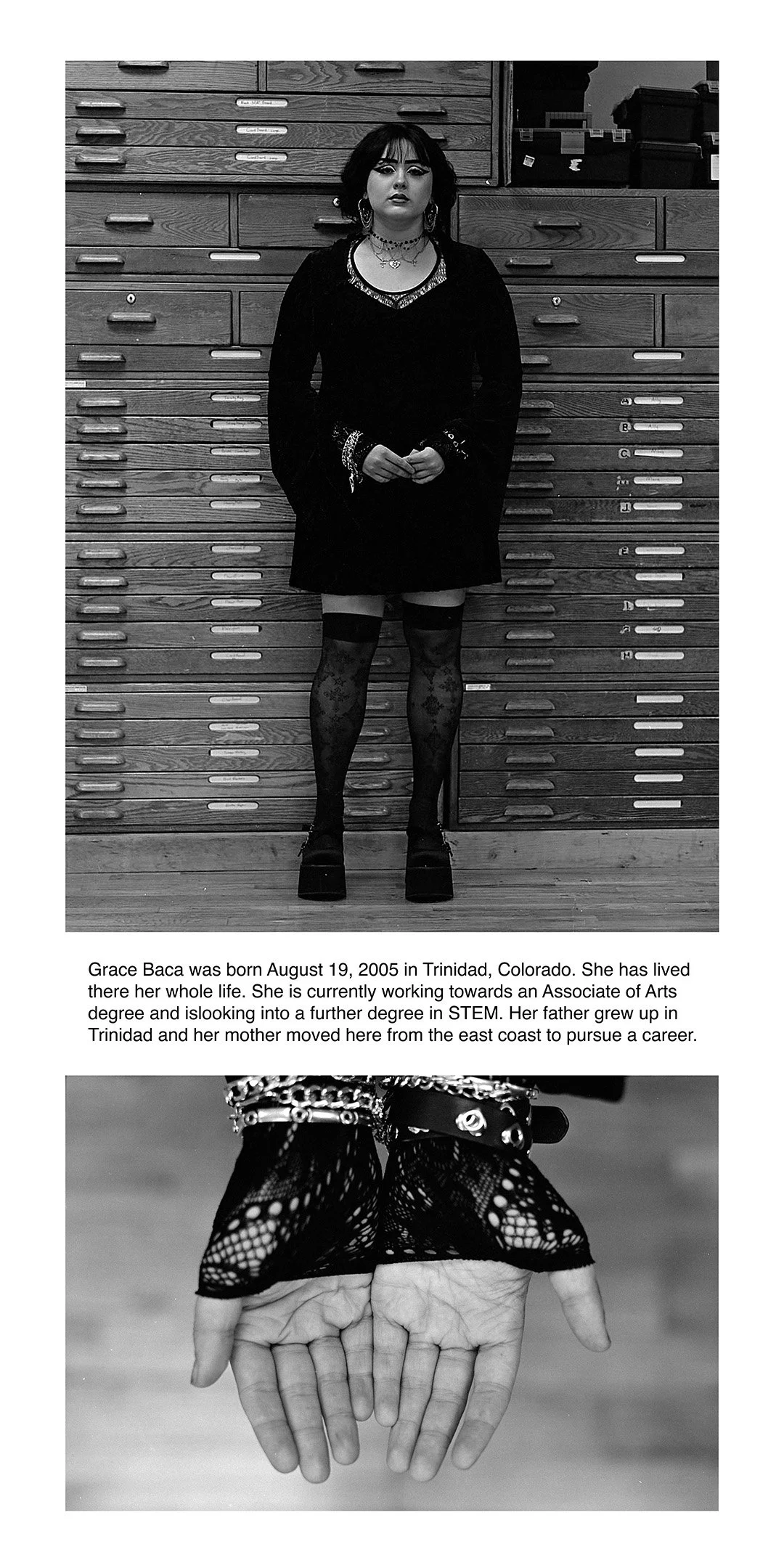

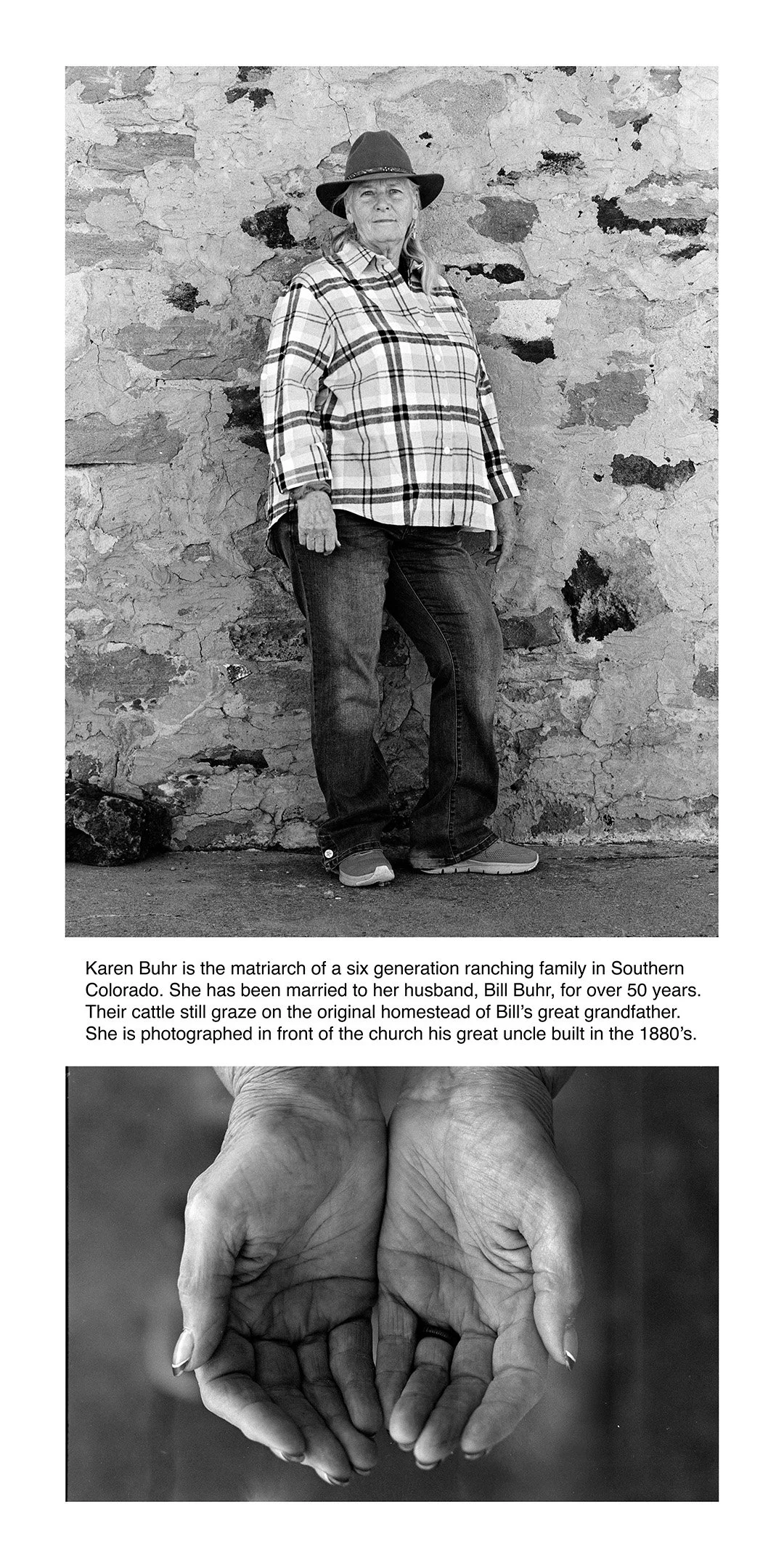

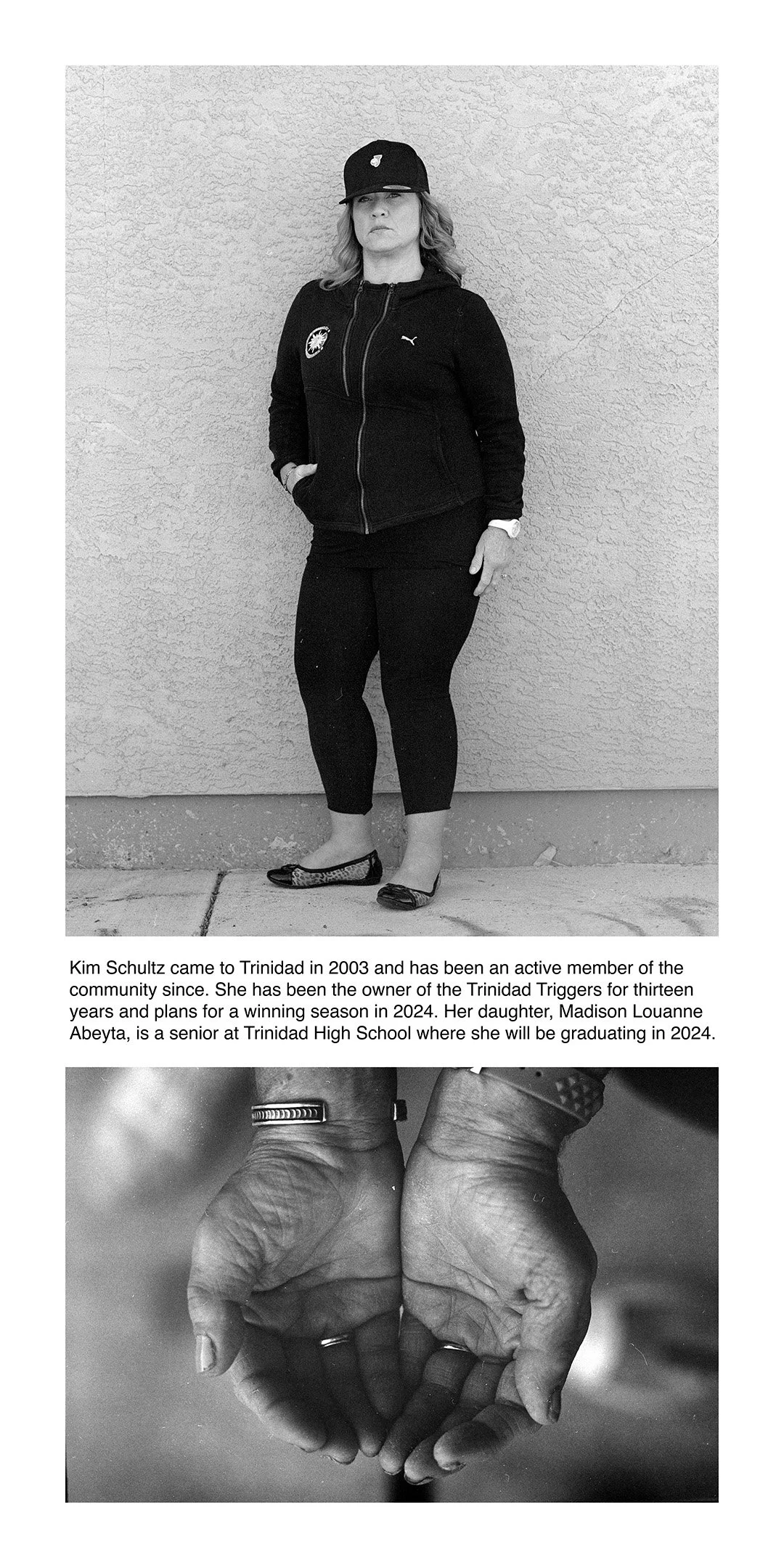

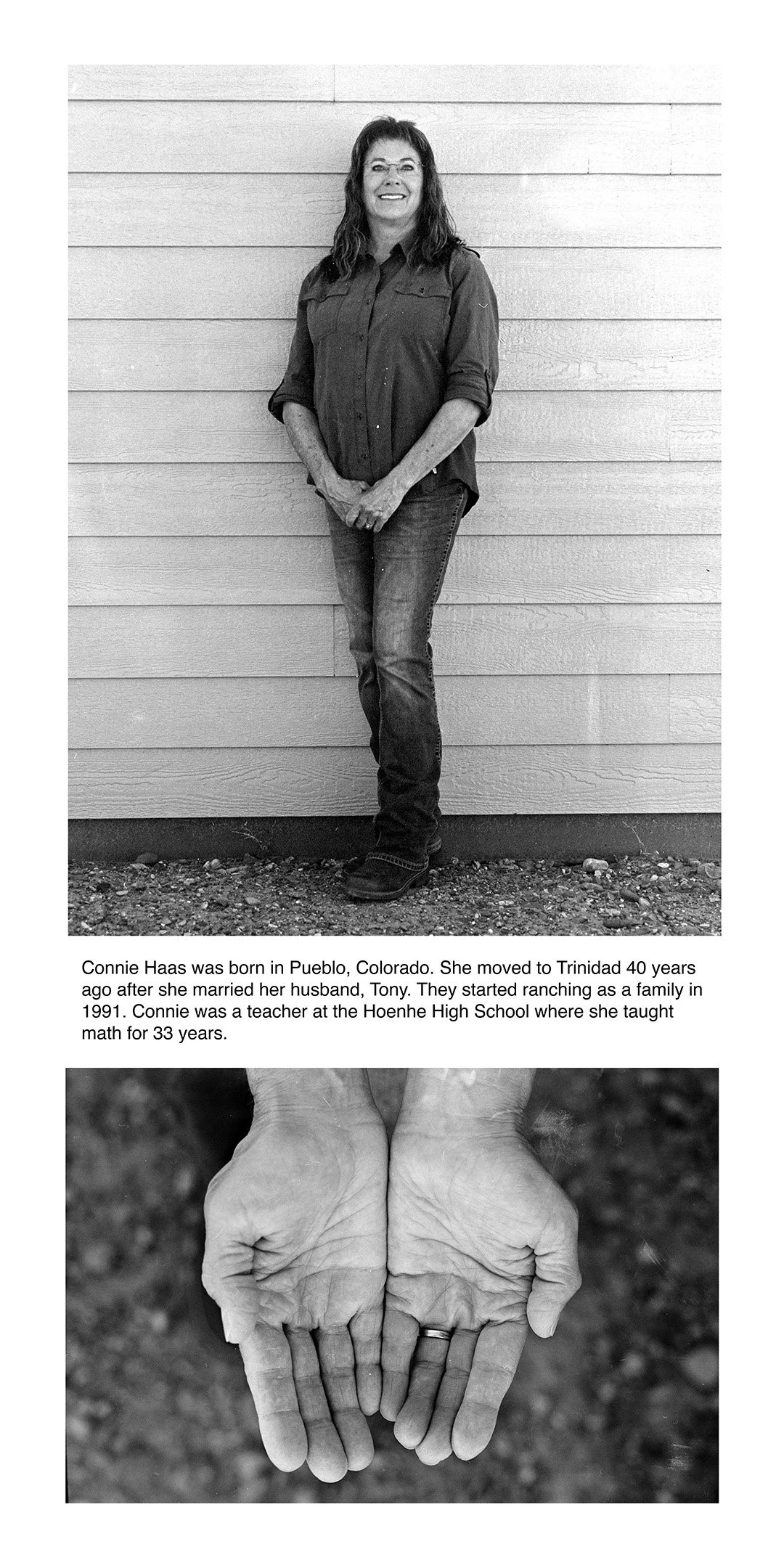

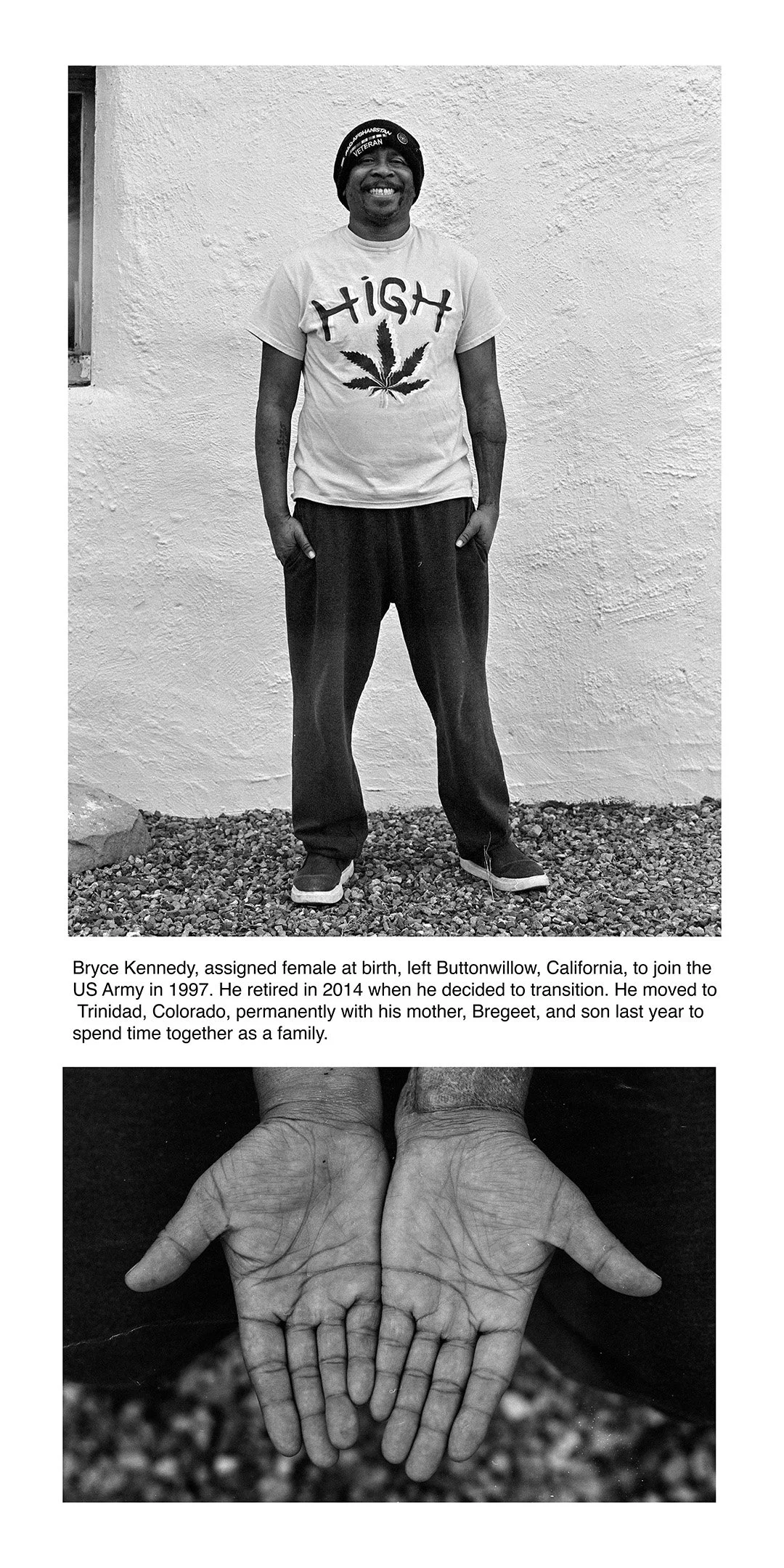

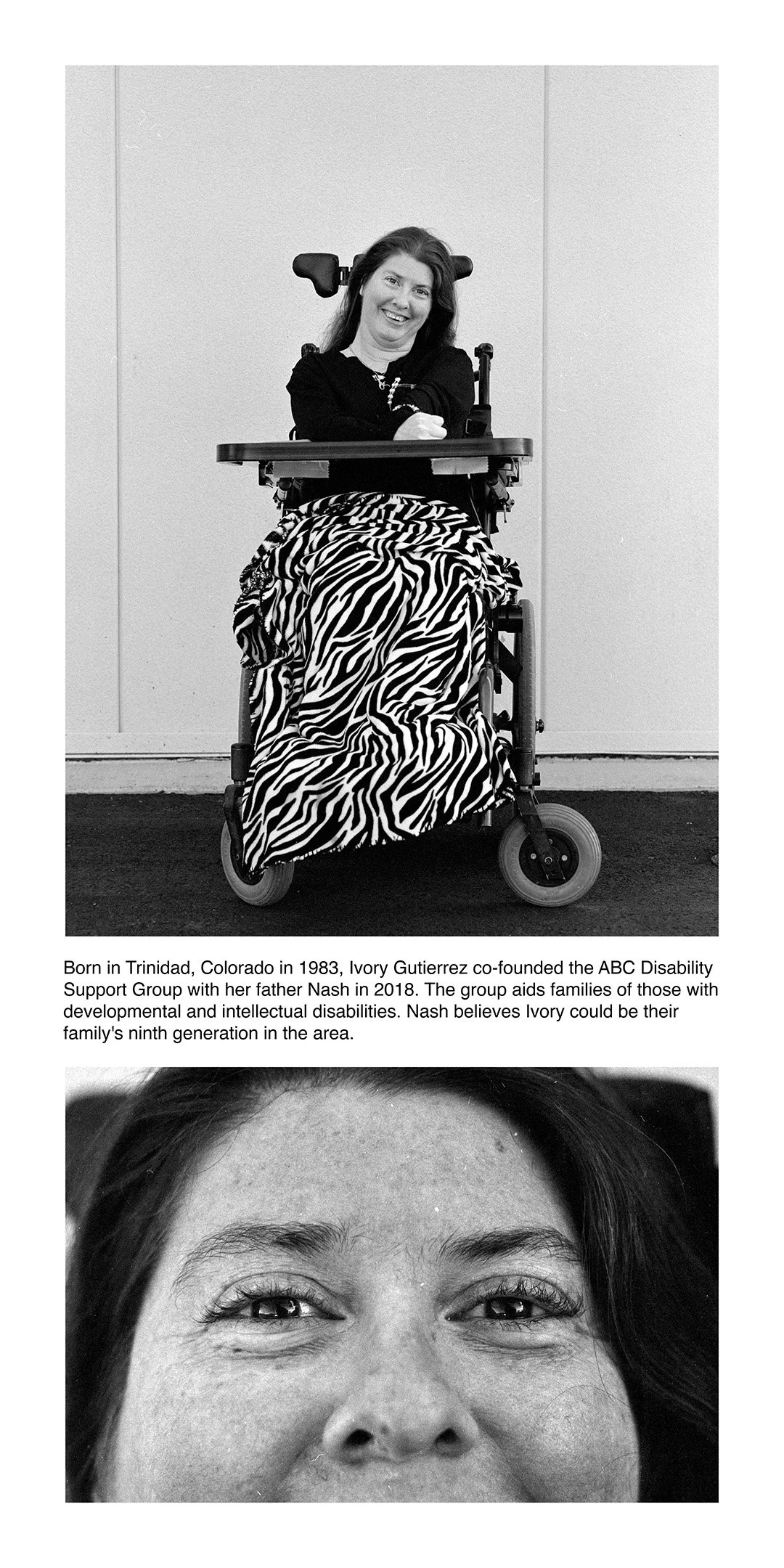

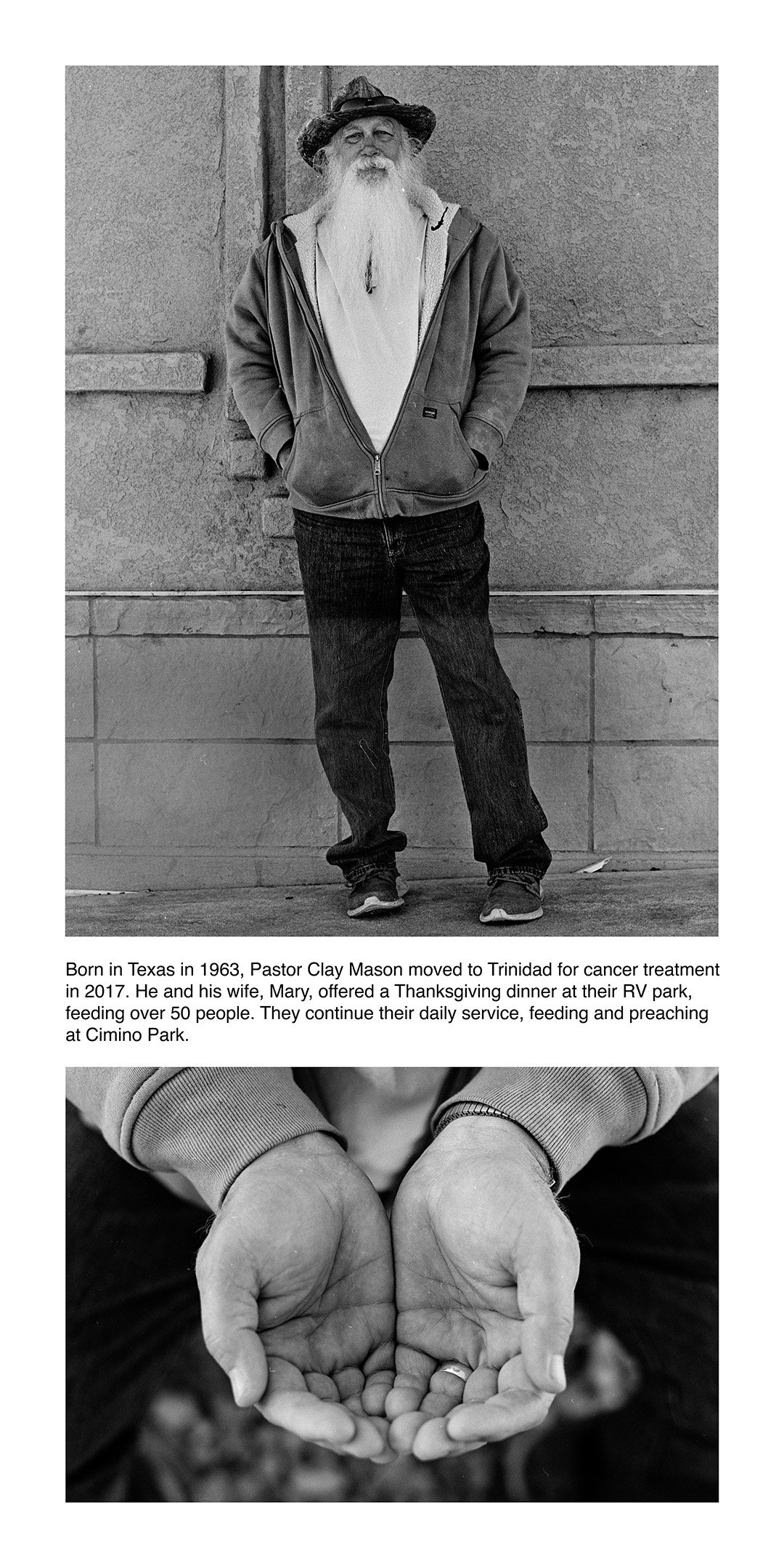

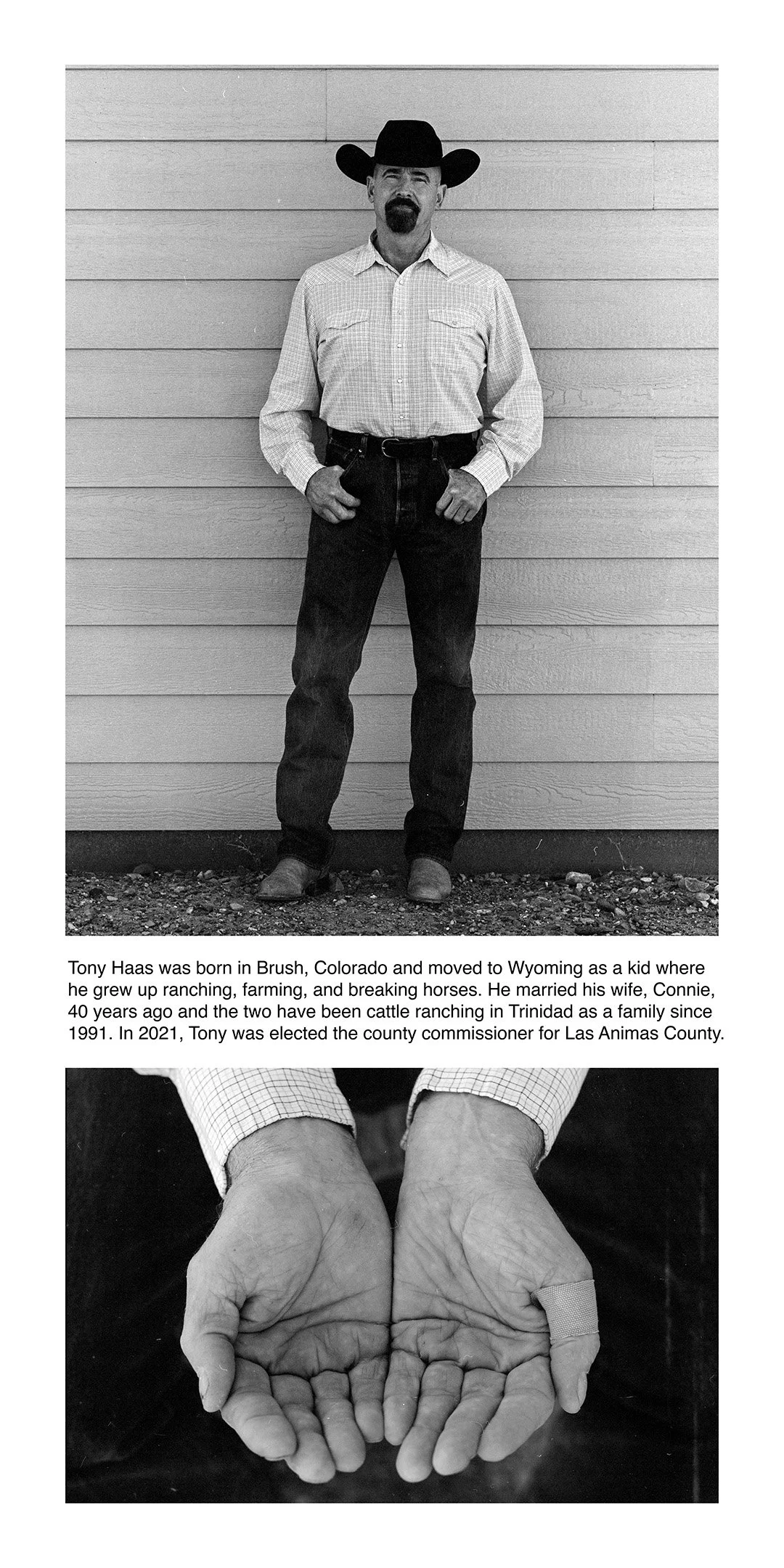

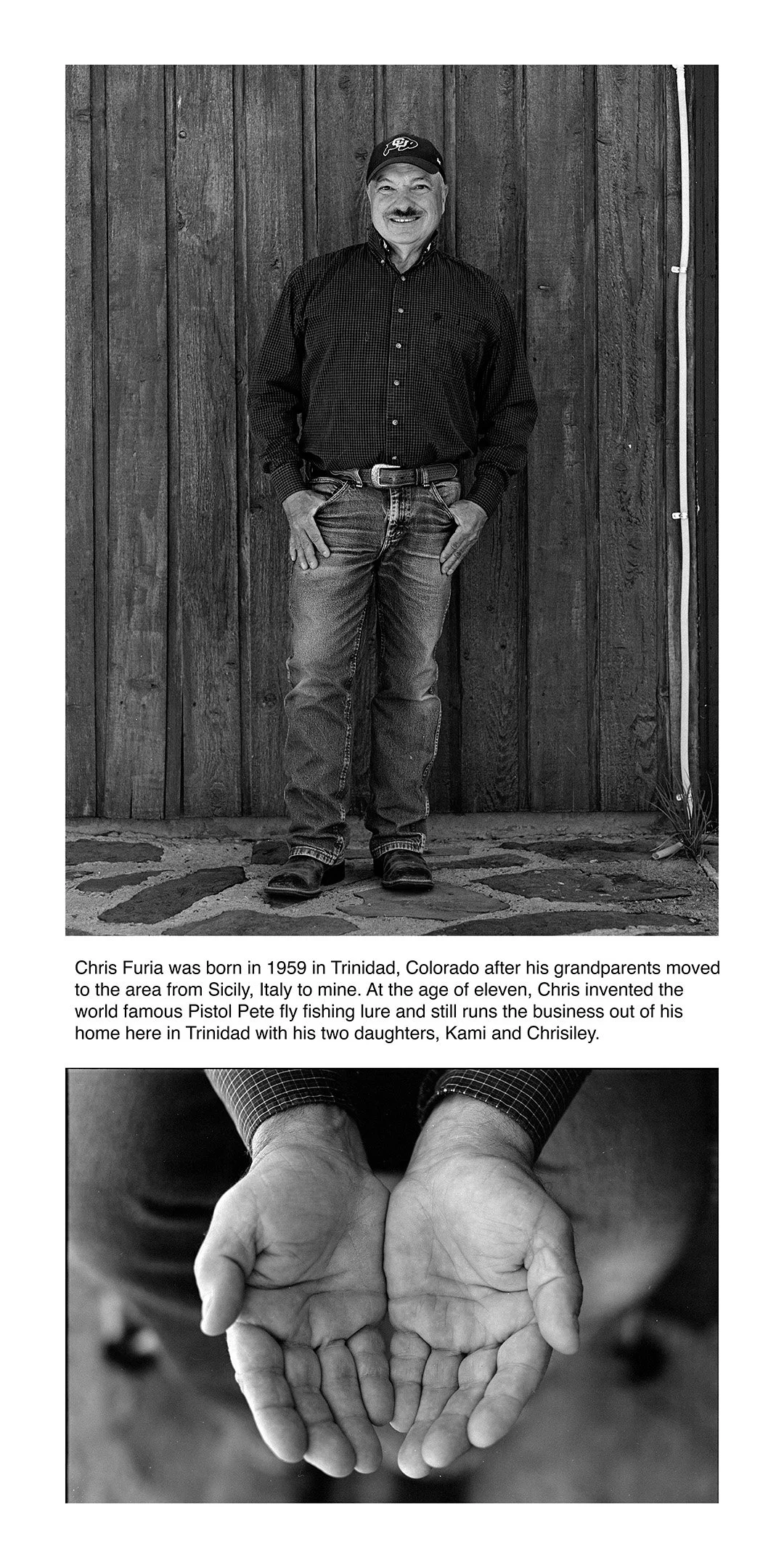

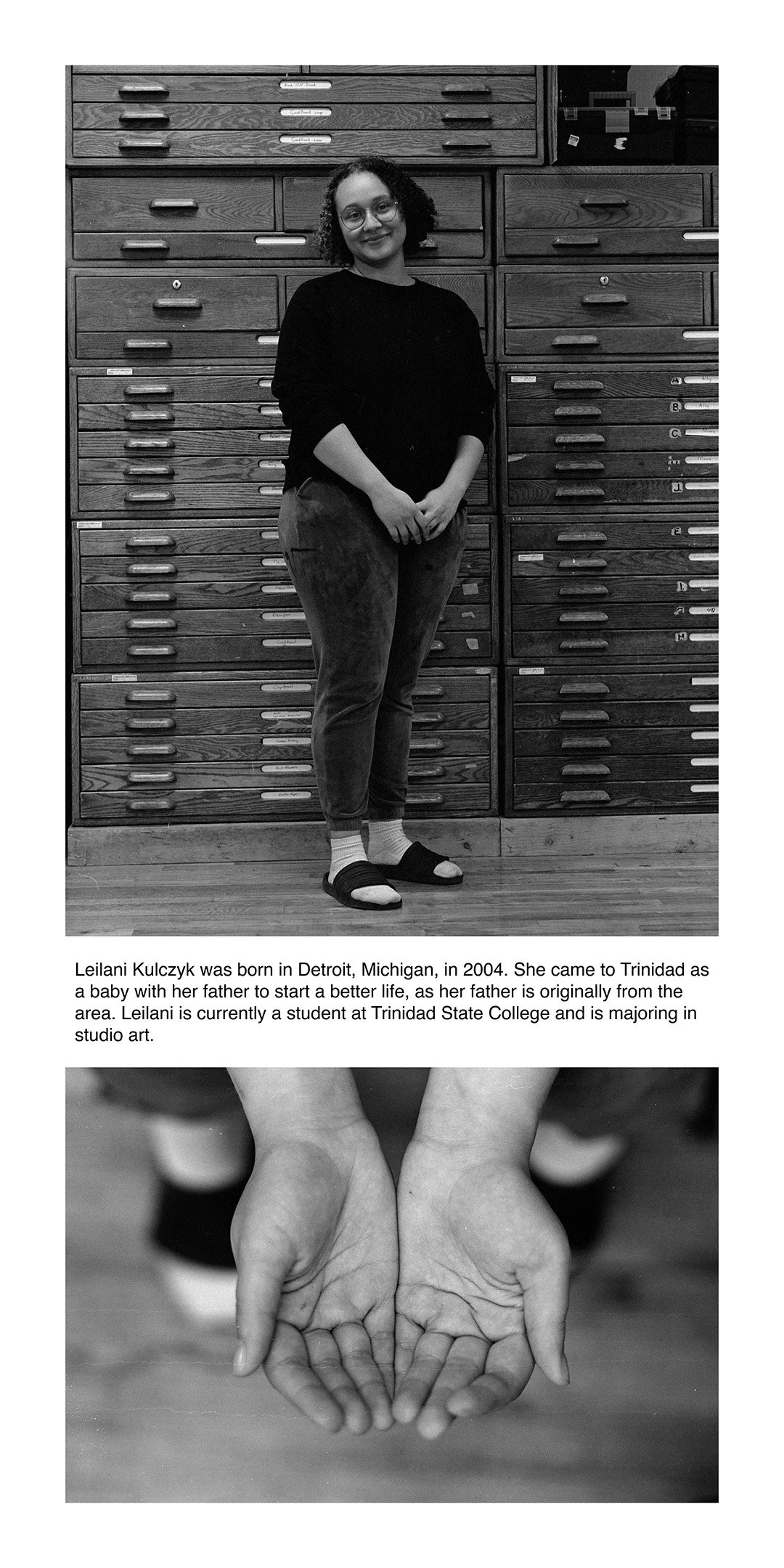

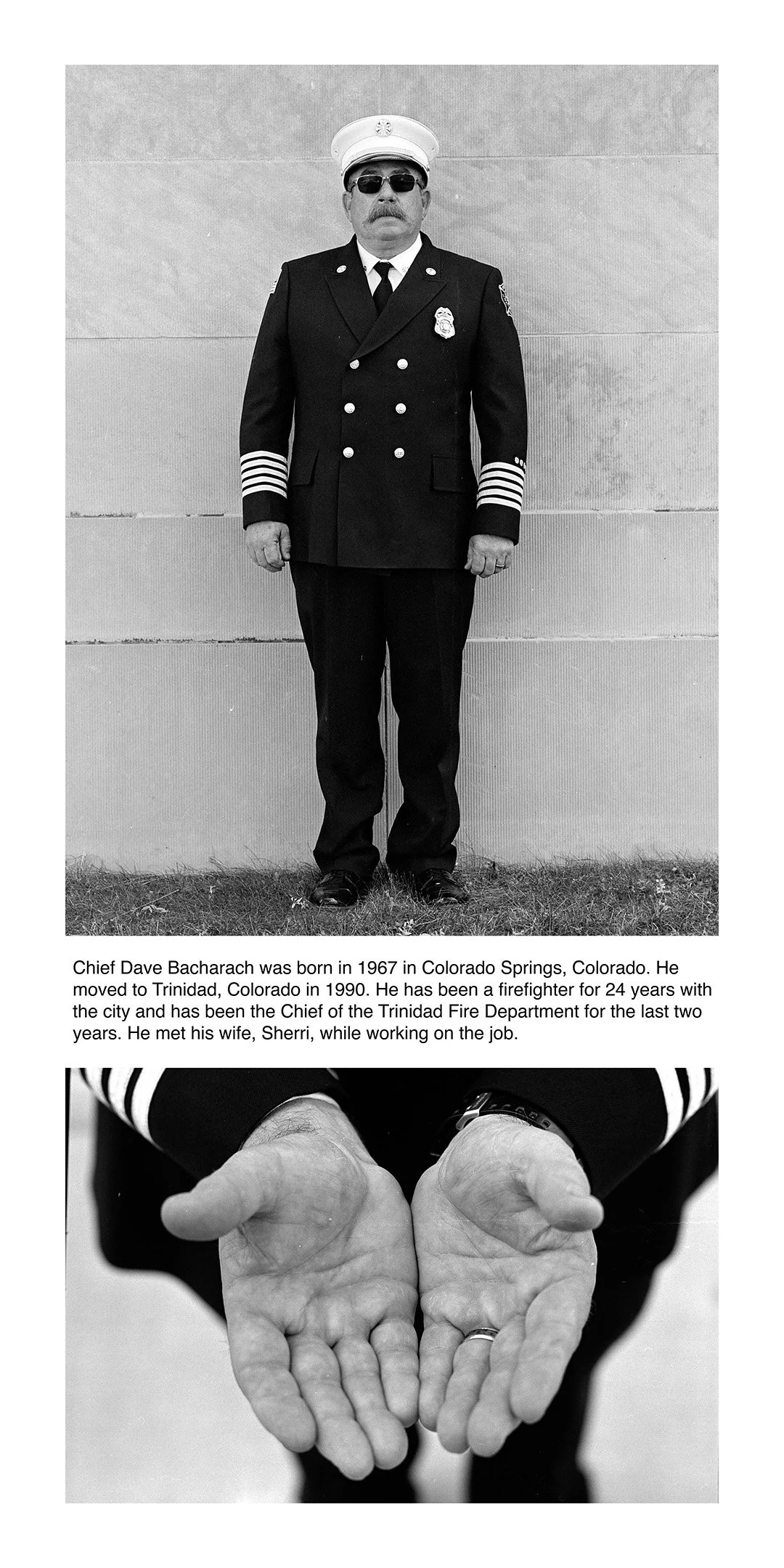

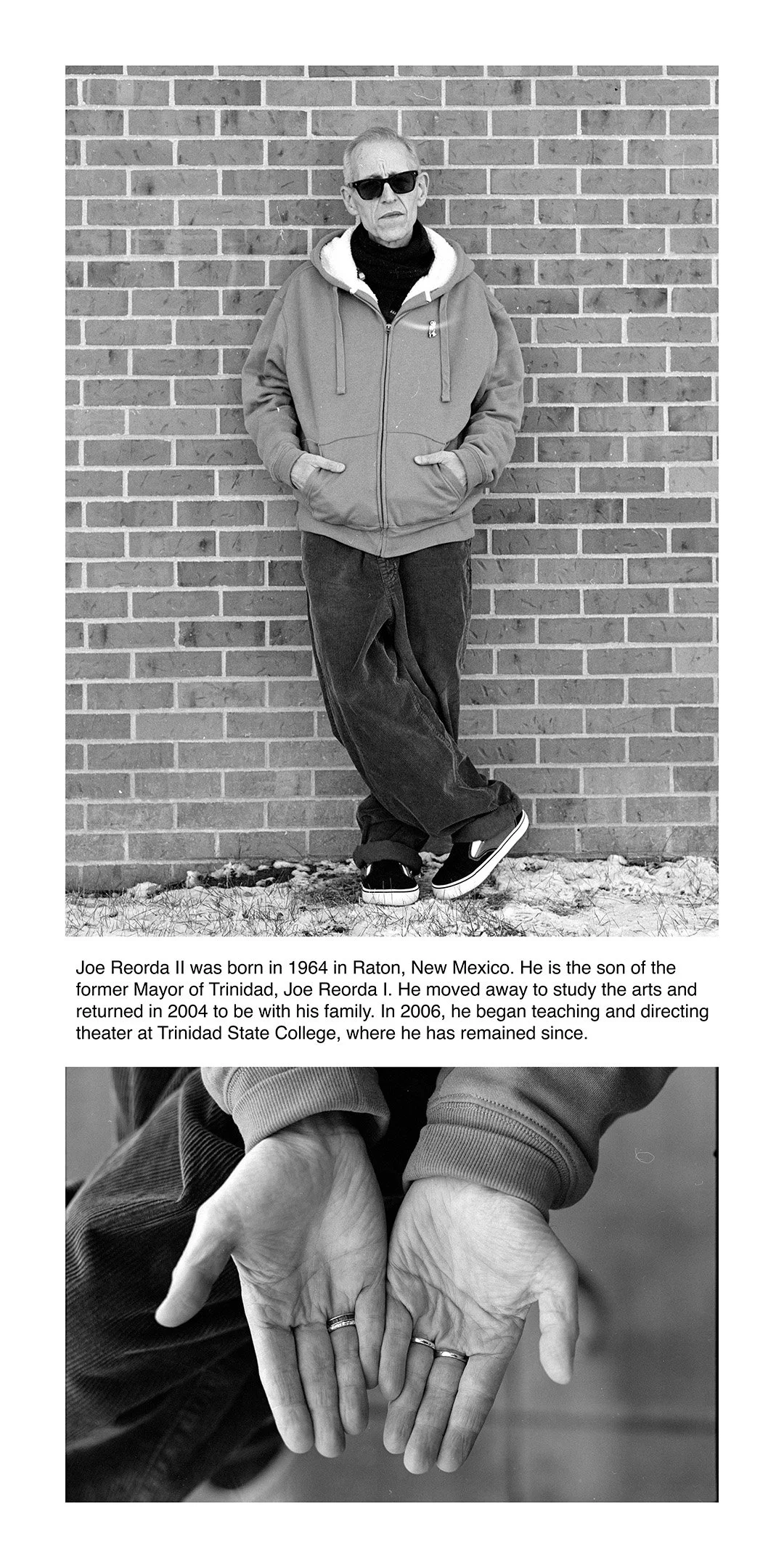

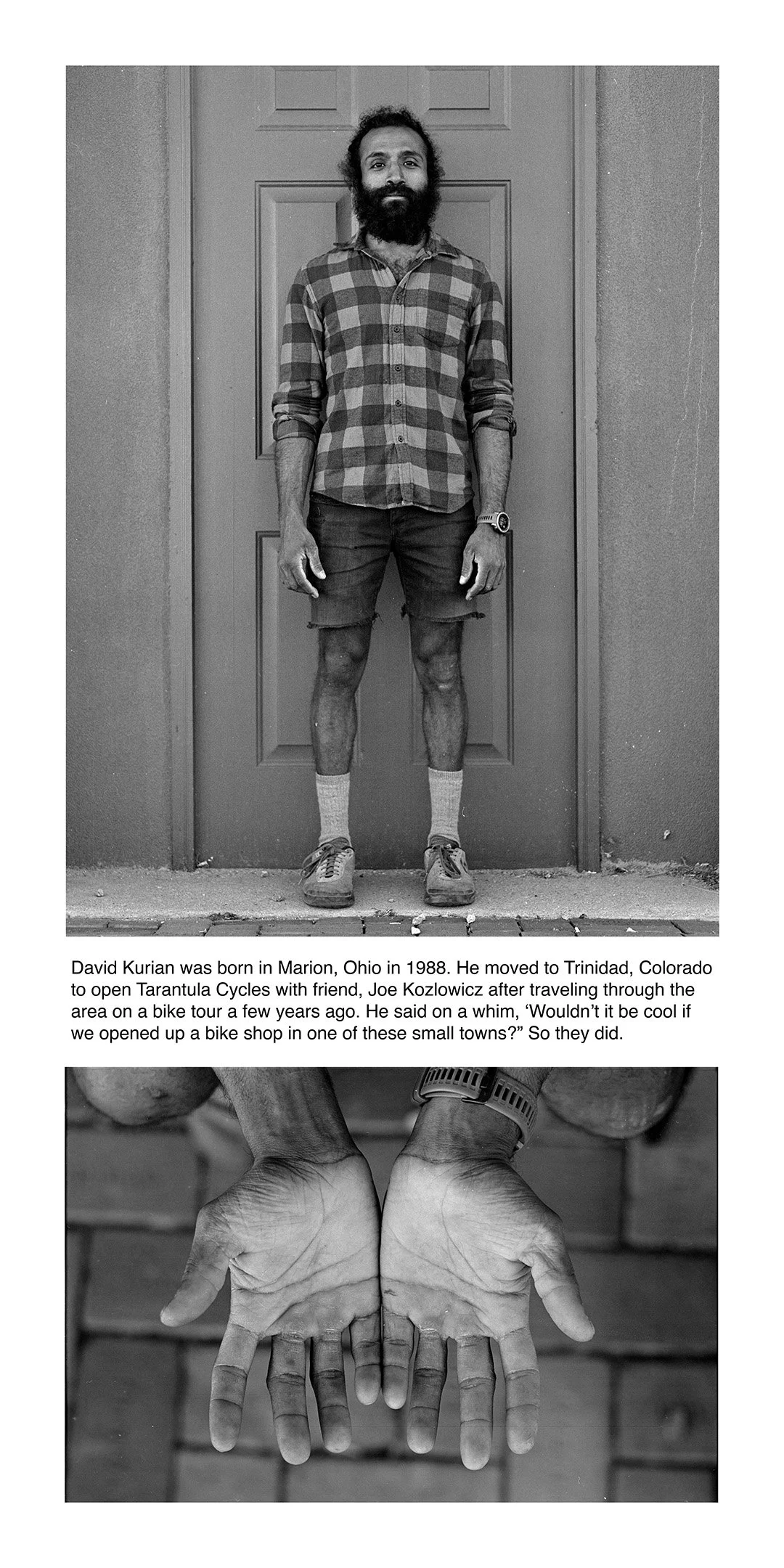

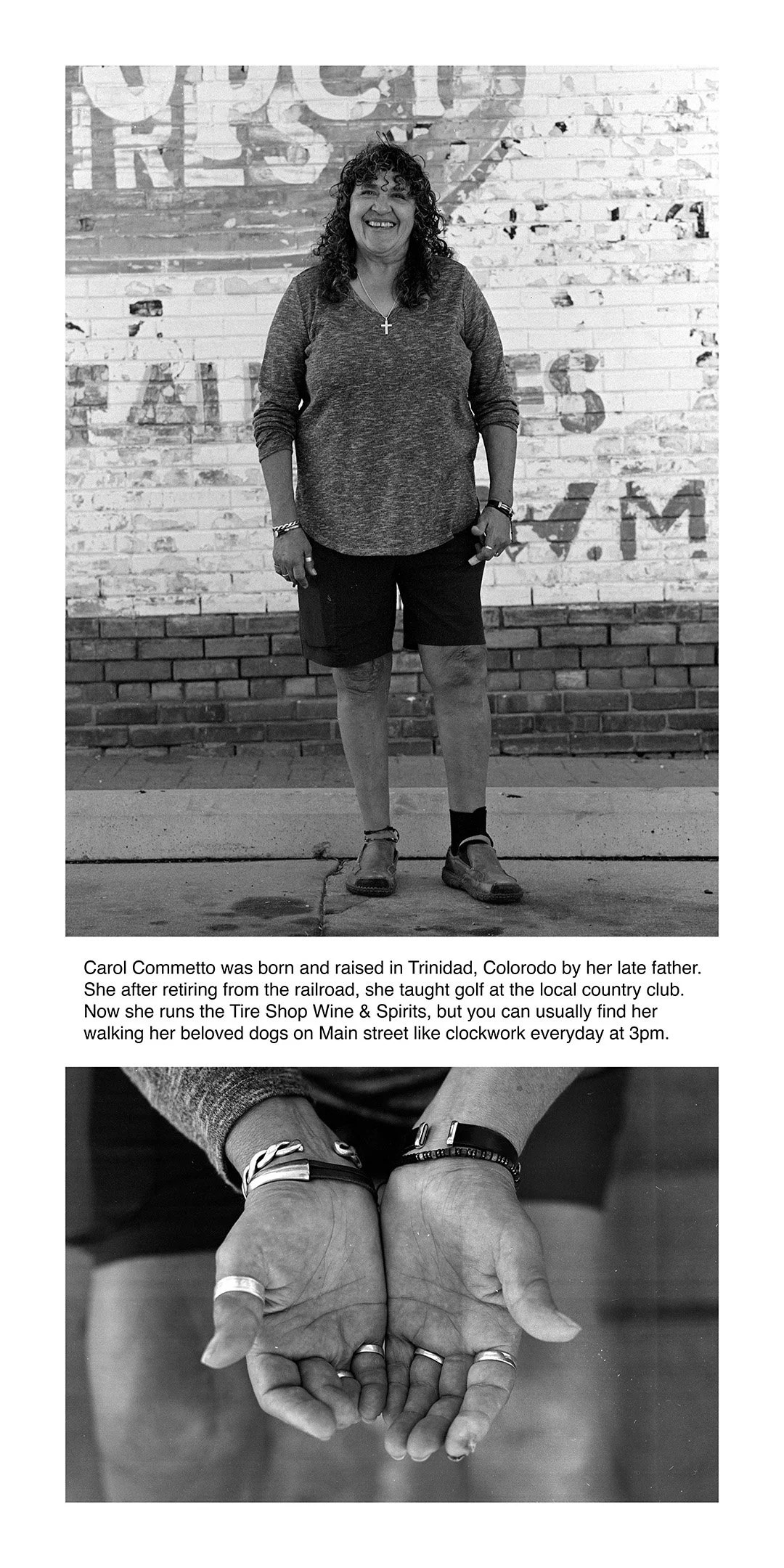

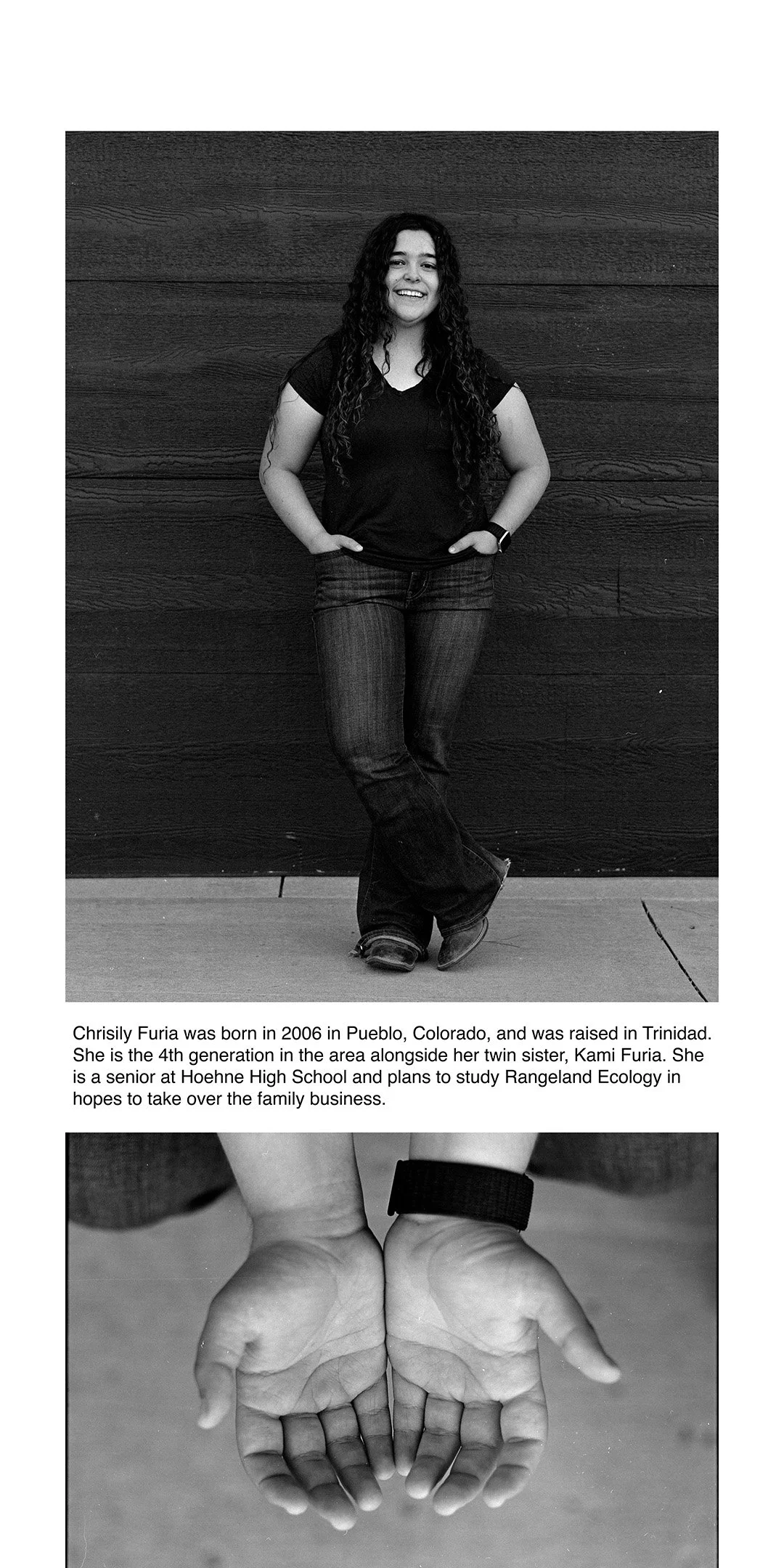

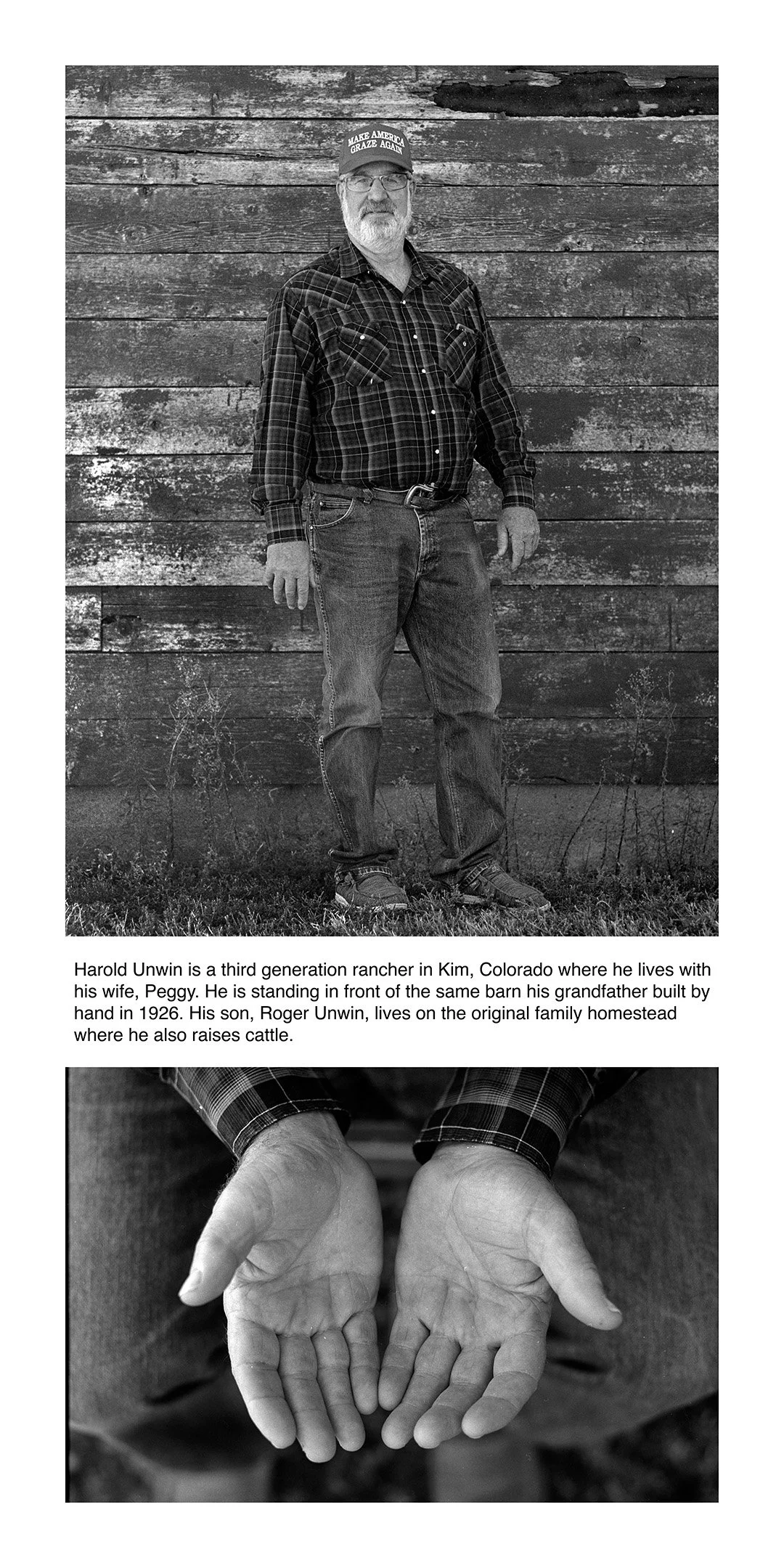

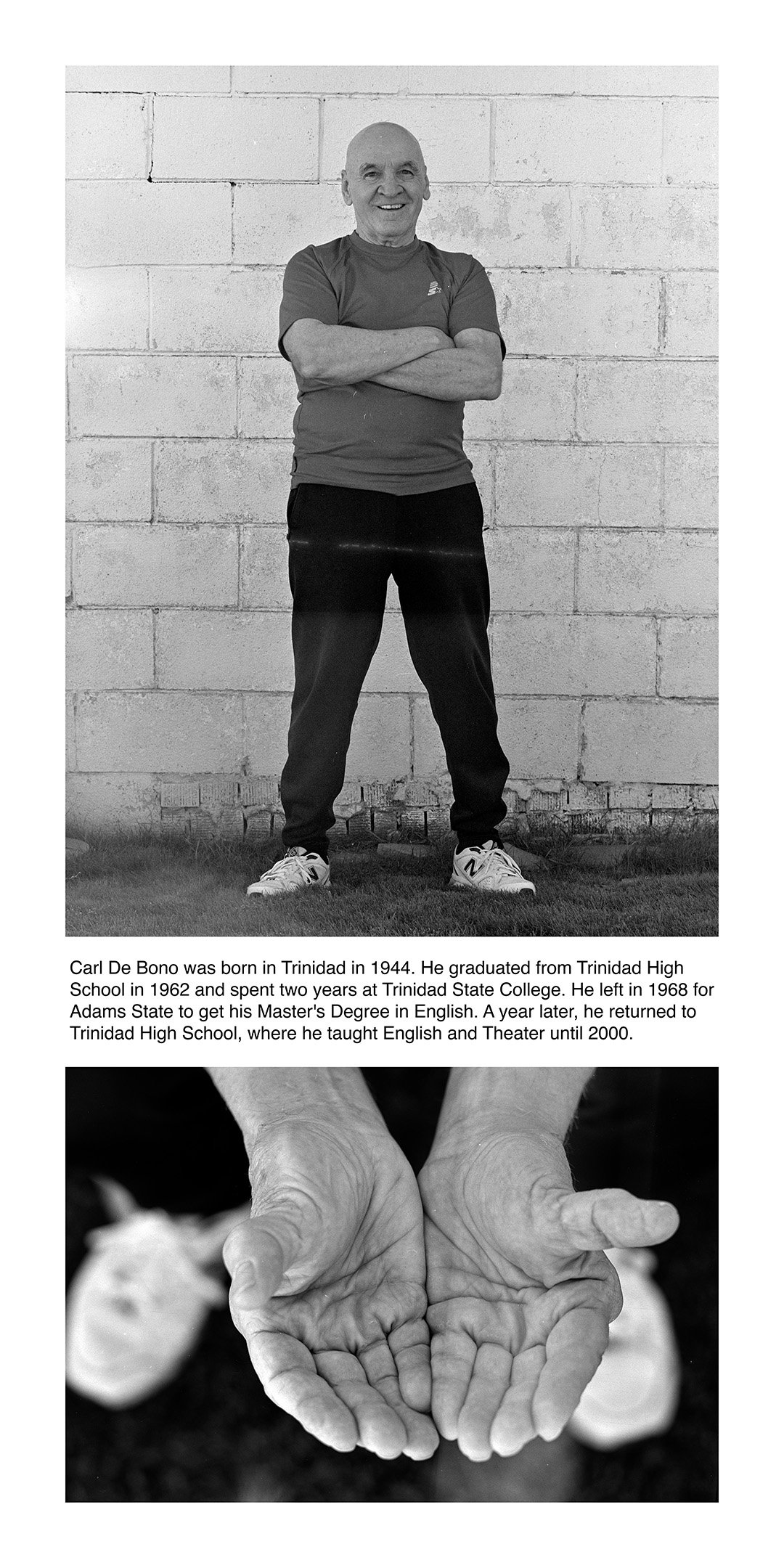

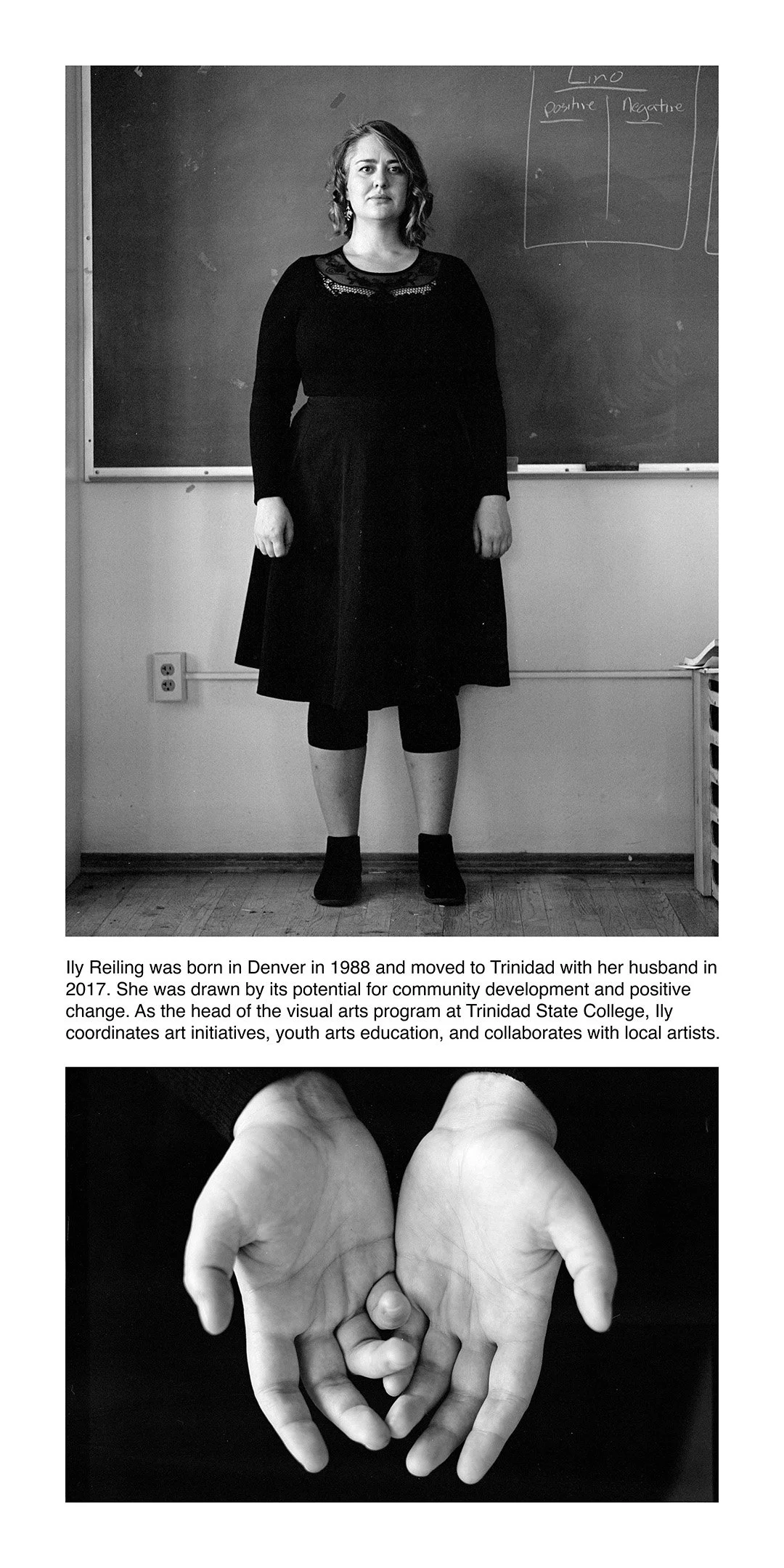

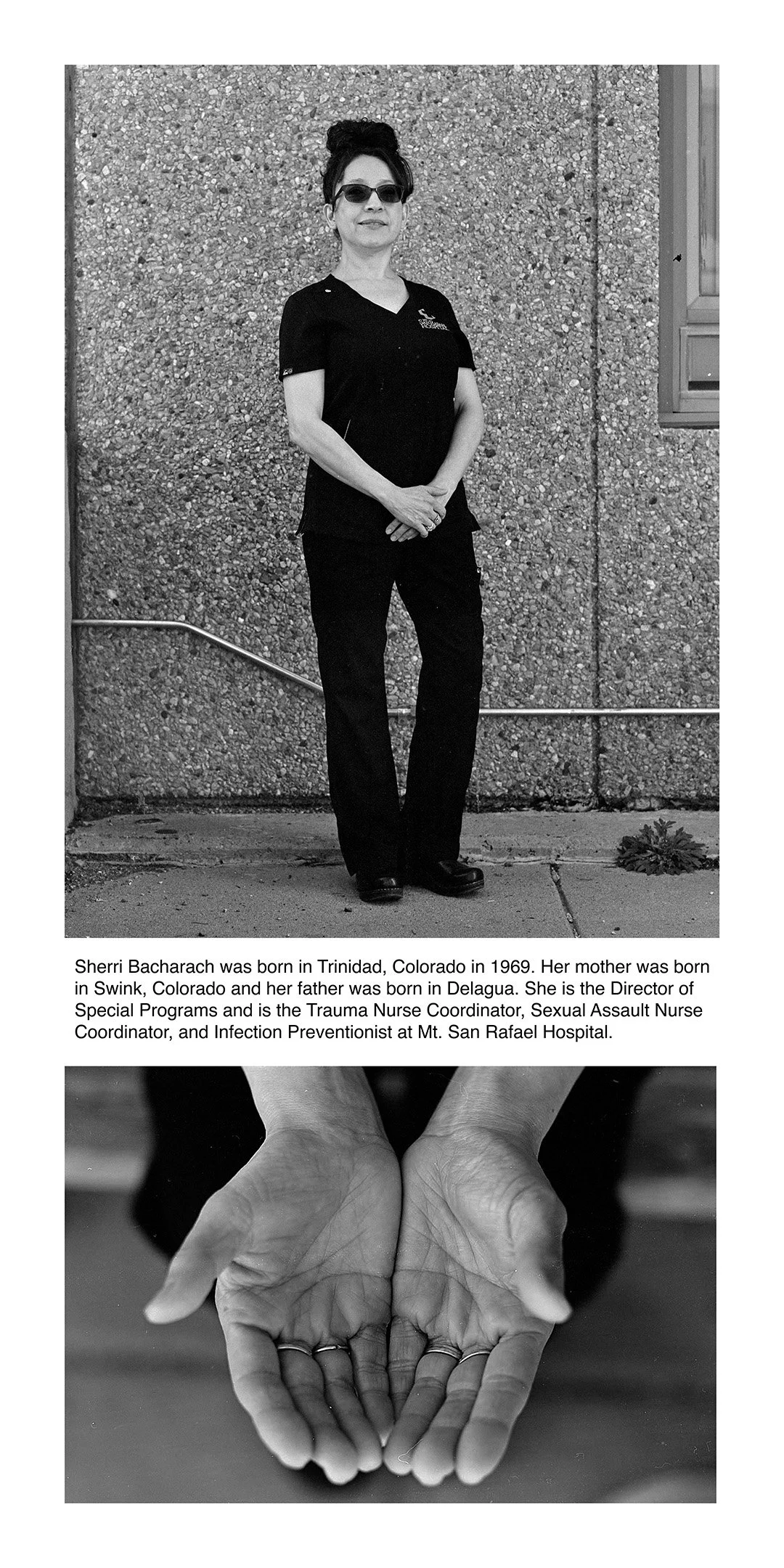

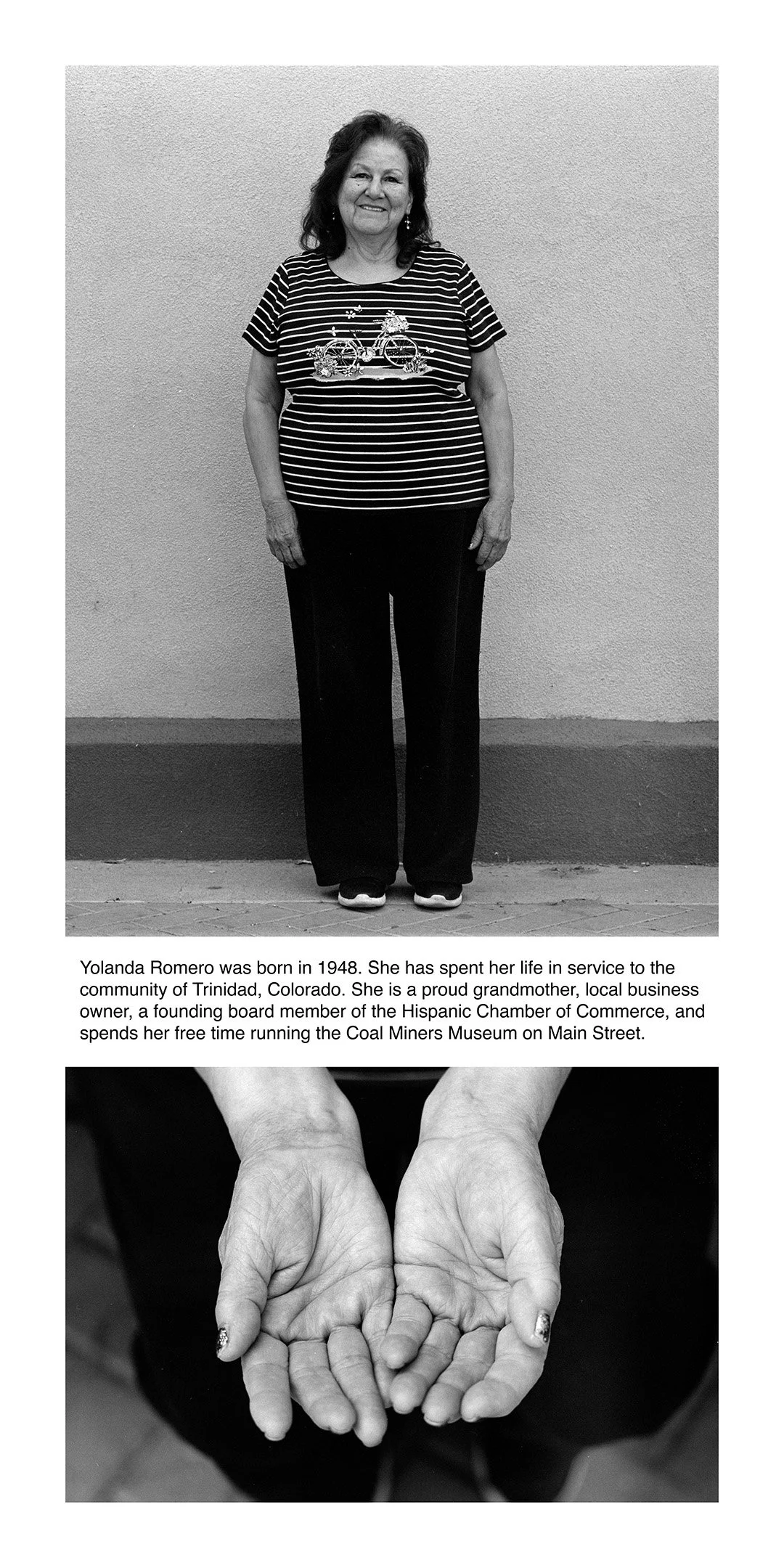

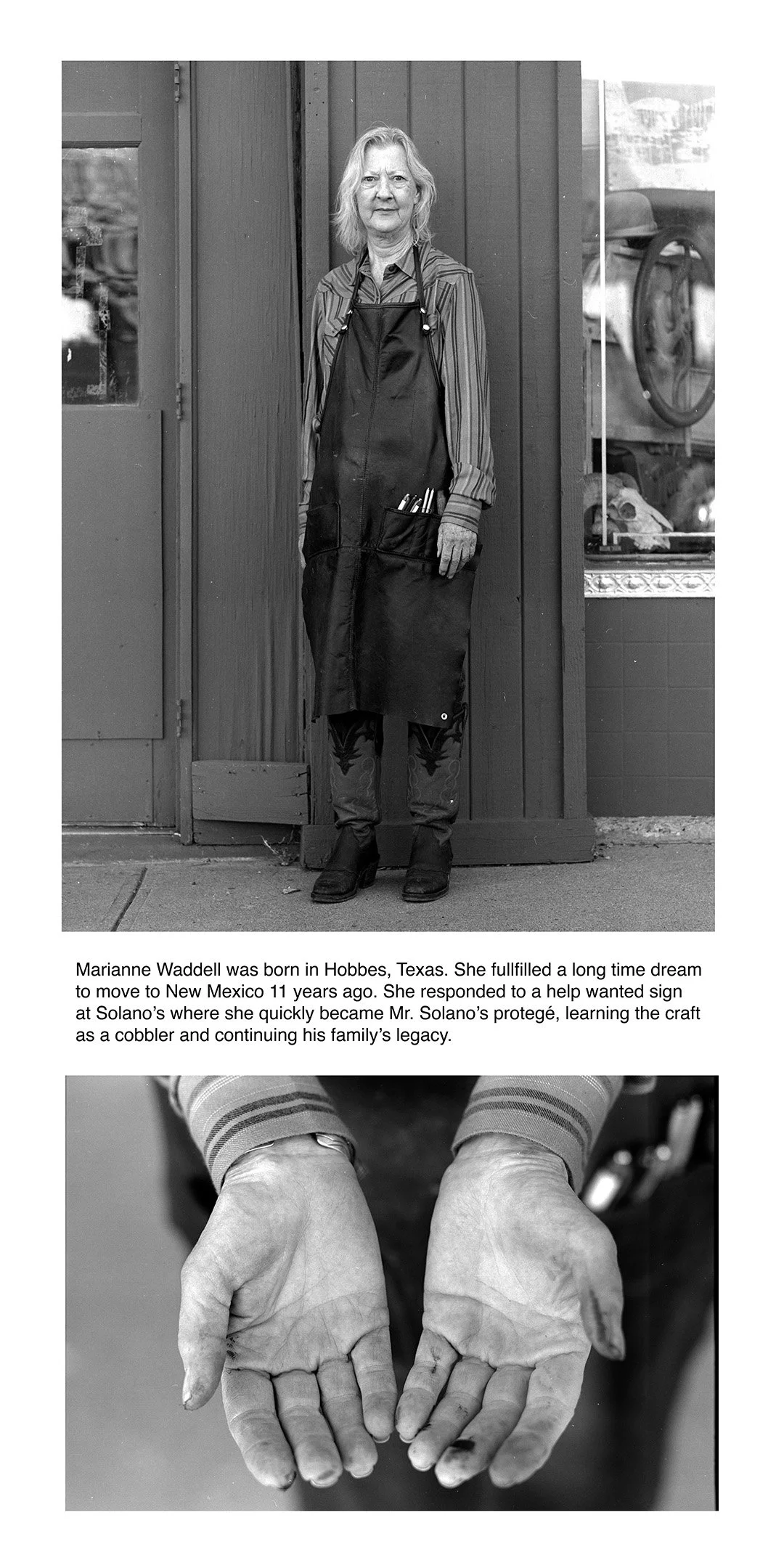

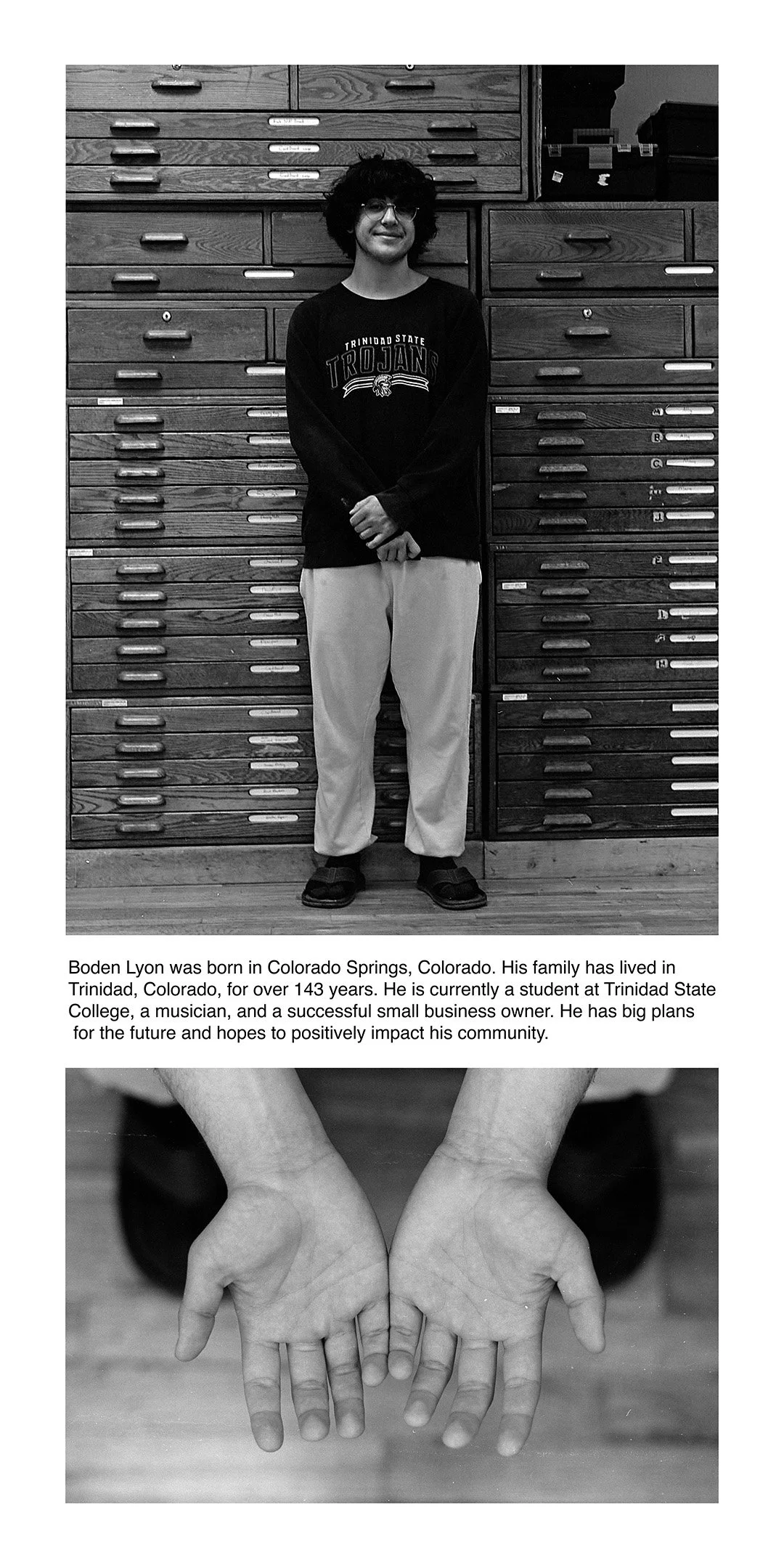

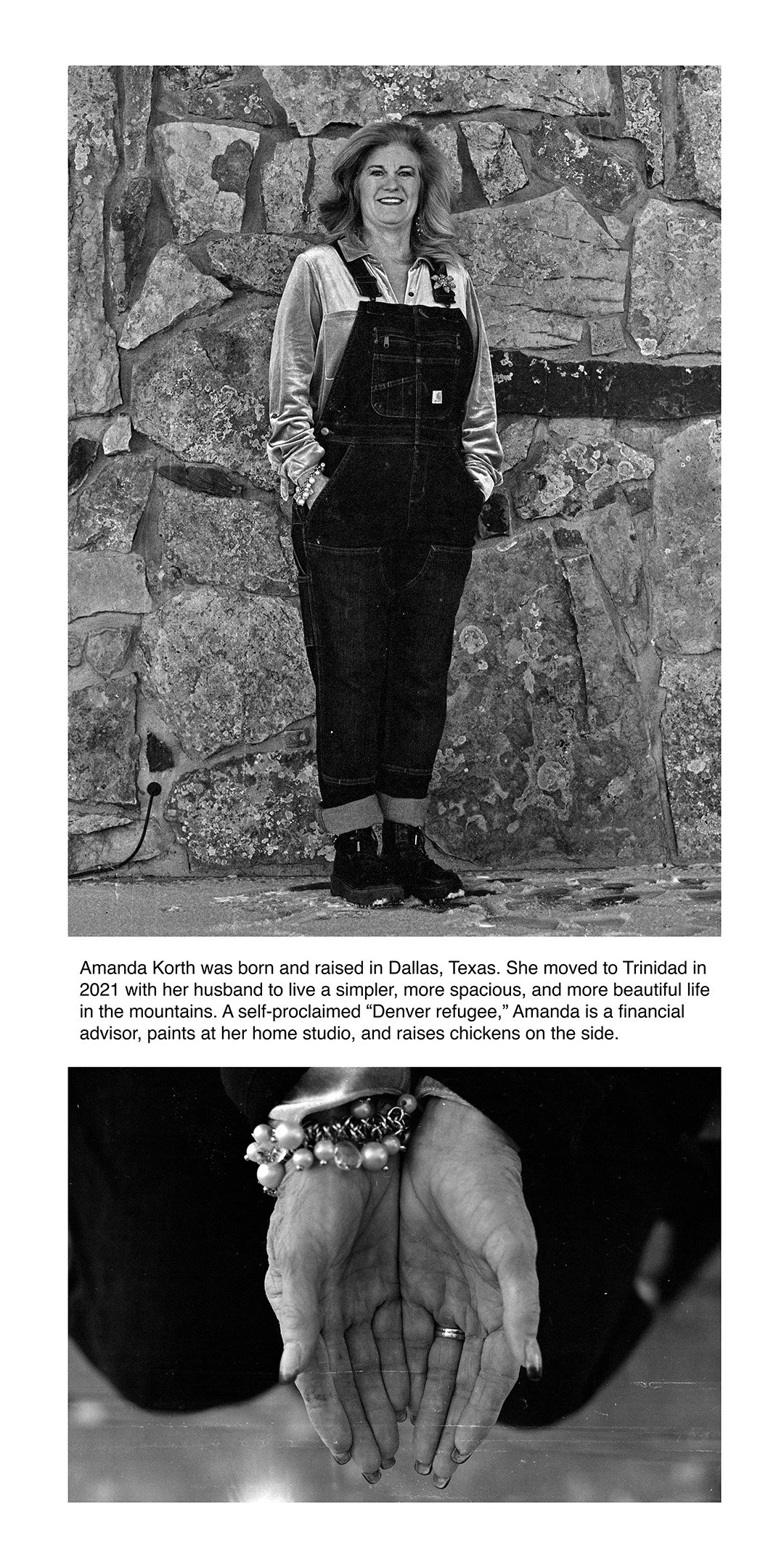

I framed the portraits methodically, like a catalog. The same margins, at the same distance, from the same height, and in the same ‘shady 8’ lighting. Through similarity, uniqueness stands out. Everybody has a fingerprint. No two are the same. I stacked each portrait with a short biography and a photo of the person's hands. The hands that laid the bricks in the road to begin with, that have kept the town alive, and that now feed the mouths of the next generation.

In the show, the images hung six feet tall by two feet wide, like human flags. Fishing lines suspended them from the rafters of Space to Create. Side-by-side, the images hovered like spirits. No particular order or sequence. No hierarchy or ranking of importance.

As I took a step back and watched people remember the moment the photo was taken, I was able to answer that initial question and say, “This is now.”

Daryl Oh, 2024